When Mary Shelley first published Frankenstein in 1818, she was just 20 years old and little did she know, her tale of a scientist’s ill-fated attempt to play God would become one of the most significant literary works in history. Nearly 200 years after its debut, Frankenstein continues to captivate audiences, with its cultural and philosophical relevance undiminished. Beyond its gothic trappings, Shelley's novel delves into profound questions about creation, responsibility, and humanity—issues as pertinent today as they were in the early 19th century.

![]()

Shelley’s Frankenstein emerged from a particularly dramatic and intellectually vibrant period in Europe. It was the year without a summer—1816—when Mount Tambora erupted, causing widespread crop failures and plummeting temperatures. Shelley's summer was spent in a villa by Lake Geneva, where she, her future husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori found themselves trapped indoors due to the dismal weather. To pass the time, the group engaged in a ghost story challenge. It was during this contest that Shelley conceived the idea for her novel, inspired by a vivid nightmare about a scientist who creates life only to be horrified by his creation.

The philosophical and scientific climate of the time played a pivotal role in shaping Shelley's narrative. The Enlightenment had left an indelible mark on society, encouraging an era of intellectual exploration and scientific discovery. In particular, the works of Luigi Galvani and Giovanni Aldini, pioneers in early galvanism, had sparked debates about the possibility of reanimating the dead. Shelley's Frankenstein draws on these developments, offering a critique of unchecked scientific ambition and the consequences of overstepping natural boundaries.

![]()

At its core, Frankenstein is not merely the story of a grotesque monster, but of isolation and the ethical dilemmas that arise when the boundaries of human knowledge are tested. Victor Frankenstein’s ambition to conquer death and unlock the secrets of life leads to a profound alienation from society, from his family, and even from himself. His creation, the Monster, is rejected by the world for its monstrous appearance, despite its innate sensitivity and desire for companionship. This tragic duality—Victor’s creation and the creature’s evolution—speaks to humanity’s fear of the "Other" and its unwillingness to confront the moral implications of science and creation.

Shelley’s novel raises timeless questions: What happens when man seeks to usurp the role of God? Is it the creator or the creation that bears the greater responsibility for moral failings? The novel's emphasis on the destructive effects of isolation, particularly the social rejection faced by the Monster, taps into the universal human fear of being alienated. Yet, Frankenstein also highlights the complexities of creation—the creator is as flawed as the creation itself, and both are subject to the unpredictable consequences of their actions.

![]()

Mary Shelley’s influence extends far beyond Frankenstein itself. Often regarded as the mother of science fiction, her exploration of science and ethics laid the groundwork for the genre's evolution, influencing later writers like H.G. Wells, Isaac Asimov, and Philip K. Dick. Shelley's blending of gothic horror with speculative science created a new literary hybrid that was both thrilling and thought-provoking.

However, it would be reductive to consider Shelley solely through the lens of Frankenstein. Her literary corpus, though smaller than that of many of her contemporaries, included works like The Last Man (1826), a post-apocalyptic narrative that explores the fall of humanity through plague—a prescient reflection on the anxieties of modernity and the fragility of civilization. Her extensive travel and intellectual engagements with the works of writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (her mother), William Godwin (her father), and Percy Bysshe Shelley, further enriched her narrative voice and political views.

As an author, Mary Shelley was both a product and a critic of her time, engaging with Romanticism's idealization of nature, the sublime, and individual genius, while simultaneously exposing the perils of excessive ambition. Her work poses deep philosophical questions, many of which remain unresolved: What does it mean to be human? What are the ethical implications of scientific progress?

![]()

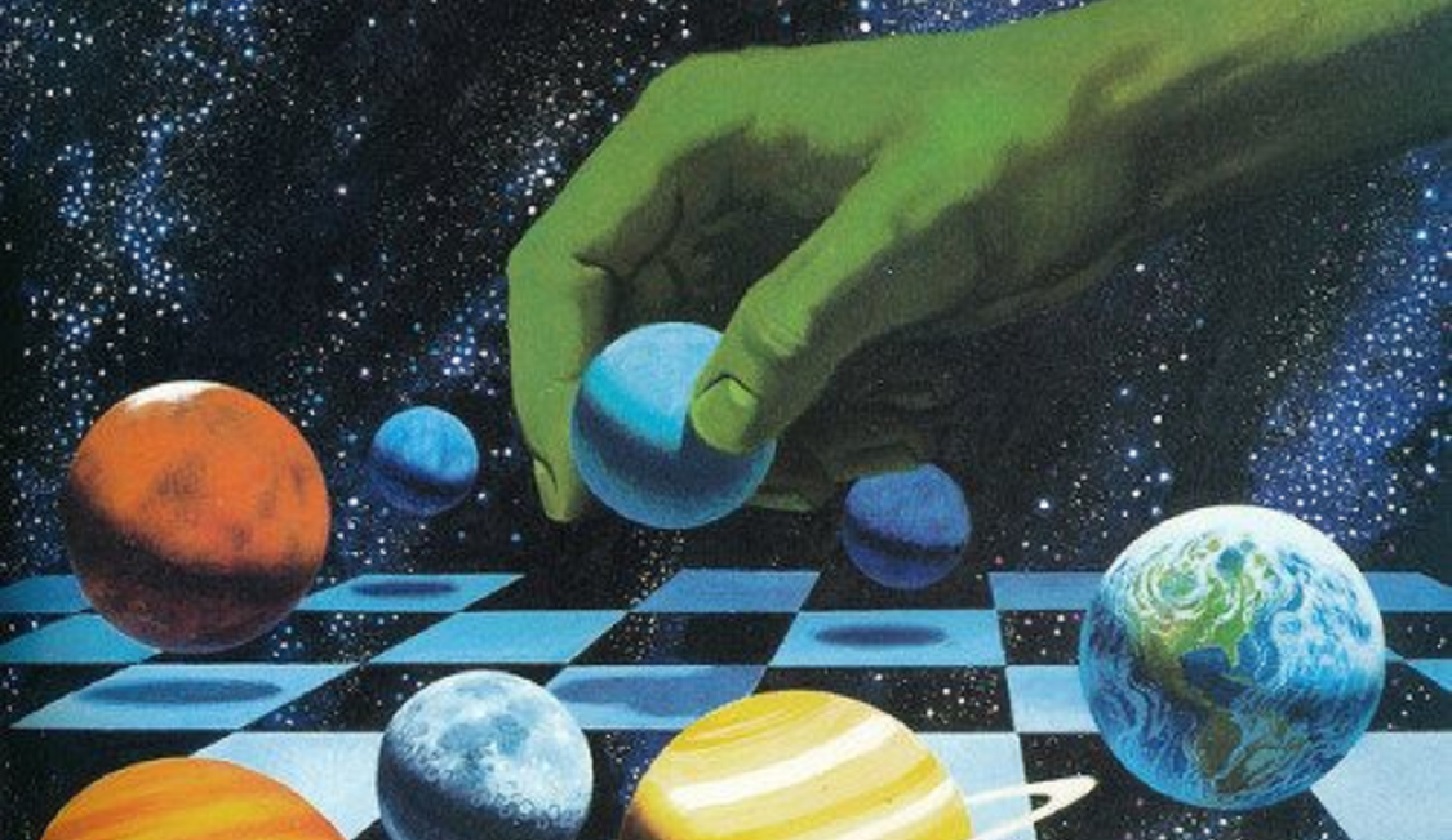

In the 21st century, Frankenstein resonates strongly, particularly within the context of technological advancements and the ethical dilemmas they raise. From genetic engineering to artificial intelligence, Shelley's questions about the limits of human knowledge and creation feel especially pertinent today. The story serves as a cautionary tale for modern society, where the rapid pace of innovation often outruns the moral frameworks that should guide it.

Moreover, the figure of the Monster—misunderstood, rejected, and ultimately vengeful—has taken on new significance in contemporary discussions about identity, exclusion, and societal responsibilities. In an age of increasing polarization and the rise of "othering" across the globe, Frankenstein invites reflection on the ways we treat those who do not fit the mainstream, those who deviate from the norm.

![]()

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein endures not only because it is a compelling narrative about monsters and madness, but because it confronts essential questions about creation, responsibility, and human nature. In examining the consequences of unchecked ambition, it serves as a warning and a mirror to the moral challenges of our time. As the boundaries of science and technology continue to stretch into uncharted territories, Shelley's novel is as vital as ever, urging us to consider the ethical ramifications of our actions and the monsters we may unintentionally create.

In the pantheon of classic literature, Frankenstein remains a touchstone, and Mary Shelley, often overshadowed by her famous male contemporaries, continues to be recognized as one of the foremost visionaries of her era.

![]()

Shelley’s Frankenstein emerged from a particularly dramatic and intellectually vibrant period in Europe. It was the year without a summer—1816—when Mount Tambora erupted, causing widespread crop failures and plummeting temperatures. Shelley's summer was spent in a villa by Lake Geneva, where she, her future husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori found themselves trapped indoors due to the dismal weather. To pass the time, the group engaged in a ghost story challenge. It was during this contest that Shelley conceived the idea for her novel, inspired by a vivid nightmare about a scientist who creates life only to be horrified by his creation.

The philosophical and scientific climate of the time played a pivotal role in shaping Shelley's narrative. The Enlightenment had left an indelible mark on society, encouraging an era of intellectual exploration and scientific discovery. In particular, the works of Luigi Galvani and Giovanni Aldini, pioneers in early galvanism, had sparked debates about the possibility of reanimating the dead. Shelley's Frankenstein draws on these developments, offering a critique of unchecked scientific ambition and the consequences of overstepping natural boundaries.

At its core, Frankenstein is not merely the story of a grotesque monster, but of isolation and the ethical dilemmas that arise when the boundaries of human knowledge are tested. Victor Frankenstein’s ambition to conquer death and unlock the secrets of life leads to a profound alienation from society, from his family, and even from himself. His creation, the Monster, is rejected by the world for its monstrous appearance, despite its innate sensitivity and desire for companionship. This tragic duality—Victor’s creation and the creature’s evolution—speaks to humanity’s fear of the "Other" and its unwillingness to confront the moral implications of science and creation.

Shelley’s novel raises timeless questions: What happens when man seeks to usurp the role of God? Is it the creator or the creation that bears the greater responsibility for moral failings? The novel's emphasis on the destructive effects of isolation, particularly the social rejection faced by the Monster, taps into the universal human fear of being alienated. Yet, Frankenstein also highlights the complexities of creation—the creator is as flawed as the creation itself, and both are subject to the unpredictable consequences of their actions.

Mary Shelley’s influence extends far beyond Frankenstein itself. Often regarded as the mother of science fiction, her exploration of science and ethics laid the groundwork for the genre's evolution, influencing later writers like H.G. Wells, Isaac Asimov, and Philip K. Dick. Shelley's blending of gothic horror with speculative science created a new literary hybrid that was both thrilling and thought-provoking.

However, it would be reductive to consider Shelley solely through the lens of Frankenstein. Her literary corpus, though smaller than that of many of her contemporaries, included works like The Last Man (1826), a post-apocalyptic narrative that explores the fall of humanity through plague—a prescient reflection on the anxieties of modernity and the fragility of civilization. Her extensive travel and intellectual engagements with the works of writers like Mary Wollstonecraft (her mother), William Godwin (her father), and Percy Bysshe Shelley, further enriched her narrative voice and political views.

As an author, Mary Shelley was both a product and a critic of her time, engaging with Romanticism's idealization of nature, the sublime, and individual genius, while simultaneously exposing the perils of excessive ambition. Her work poses deep philosophical questions, many of which remain unresolved: What does it mean to be human? What are the ethical implications of scientific progress?

In the 21st century, Frankenstein resonates strongly, particularly within the context of technological advancements and the ethical dilemmas they raise. From genetic engineering to artificial intelligence, Shelley's questions about the limits of human knowledge and creation feel especially pertinent today. The story serves as a cautionary tale for modern society, where the rapid pace of innovation often outruns the moral frameworks that should guide it.

Moreover, the figure of the Monster—misunderstood, rejected, and ultimately vengeful—has taken on new significance in contemporary discussions about identity, exclusion, and societal responsibilities. In an age of increasing polarization and the rise of "othering" across the globe, Frankenstein invites reflection on the ways we treat those who do not fit the mainstream, those who deviate from the norm.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein endures not only because it is a compelling narrative about monsters and madness, but because it confronts essential questions about creation, responsibility, and human nature. In examining the consequences of unchecked ambition, it serves as a warning and a mirror to the moral challenges of our time. As the boundaries of science and technology continue to stretch into uncharted territories, Shelley's novel is as vital as ever, urging us to consider the ethical ramifications of our actions and the monsters we may unintentionally create.

In the pantheon of classic literature, Frankenstein remains a touchstone, and Mary Shelley, often overshadowed by her famous male contemporaries, continues to be recognized as one of the foremost visionaries of her era.