The Epic of Gilgamesh is not merely a work of ancient literature—it is a cornerstone of human storytelling, one whose resonance transcends millennia. Originating in Mesopotamia, this poem offers a glimpse into the world of Sumerian and Akkadian culture around 2000 BCE, and in doing so, it provides an understanding of the human condition that feels as relevant today as it did in antiquity.

But beyond its historical importance, the Epic of Gilgamesh captures a time in which humanity’s wrestle with mortality, the desire for immortality, and the struggle to comprehend the divine were central to understanding the world. To those who lived in the shadow of the great ziggurats of Sumer, these stories weren’t just entertainment; they were blueprints for how to navigate life’s most pressing questions.

At the heart of the Epic of Gilgamesh is an exploration of human vulnerability—its reflection on death, love, friendship, and the meaning of life places it as one of the first great literary works that answers the perennial question: "What does it mean to be human?"

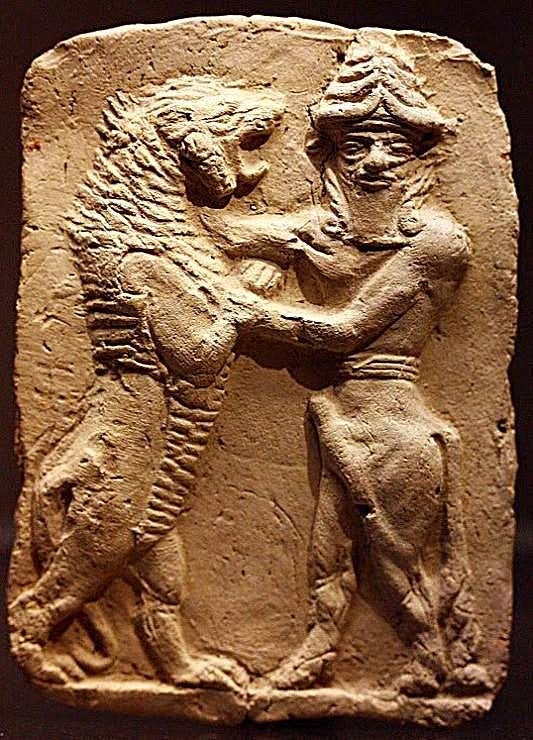

The hero, Gilgamesh, a semi-divine king of Uruk, embarks on a journey not merely for conquest or glory, but for immortality. His journey introduces a cast of characters that mirror the complexities of life and death, most notably Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods to temper Gilgamesh’s arrogance. Their deep friendship serves as a catalyst for Gilgamesh’s self-discovery and is arguably one of the most poignant depictions of camaraderie in ancient literature.

But it is Enkidu’s death that catapults the king into an existential crisis, forcing him to confront the limits of his own power. The epic, through Gilgamesh’s quest for eternal life, teaches that immortality, if not in the literal sense, can be achieved through legacy—through the deeds we leave behind. This theme has reverberated through countless other cultures and continues to speak to modern readers grappling with the fragility of life.

The hero, Gilgamesh, a semi-divine king of Uruk, embarks on a journey not merely for conquest or glory, but for immortality. His journey introduces a cast of characters that mirror the complexities of life and death, most notably Enkidu, a wild man created by the gods to temper Gilgamesh’s arrogance. Their deep friendship serves as a catalyst for Gilgamesh’s self-discovery and is arguably one of the most poignant depictions of camaraderie in ancient literature.

But it is Enkidu’s death that catapults the king into an existential crisis, forcing him to confront the limits of his own power. The epic, through Gilgamesh’s quest for eternal life, teaches that immortality, if not in the literal sense, can be achieved through legacy—through the deeds we leave behind. This theme has reverberated through countless other cultures and continues to speak to modern readers grappling with the fragility of life.

The Epic of Gilgamesh also serves as a cultural document that reflects the values, customs, and religious beliefs of ancient Mesopotamia. At the core of Gilgamesh’s identity is the tension between his divine and mortal halves, a microcosm of the larger societal ideals. This tension highlights Mesopotamian views on kingship, where rulers were often seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, expected to lead with wisdom, bravery, and justice.

Moreover, the epic touches upon the role of the gods, their whims, and the relationship between humanity and the divine. The gods in Gilgamesh are not omnipotent and benevolent but are capricious beings whose actions reflect the unpredictable nature of the world. In this, the poem speaks to the Mesopotamian understanding that human life is fragile, often shaped by forces beyond one’s control.

Through Gilgamesh’s character arc—moving from a self-centered, tyrannical leader to a figure of wisdom and humility—the epic becomes a cautionary tale about the responsibilities of power and the importance of living justly.

Moreover, the epic touches upon the role of the gods, their whims, and the relationship between humanity and the divine. The gods in Gilgamesh are not omnipotent and benevolent but are capricious beings whose actions reflect the unpredictable nature of the world. In this, the poem speaks to the Mesopotamian understanding that human life is fragile, often shaped by forces beyond one’s control.

Through Gilgamesh’s character arc—moving from a self-centered, tyrannical leader to a figure of wisdom and humility—the epic becomes a cautionary tale about the responsibilities of power and the importance of living justly.

While the Epic of Gilgamesh remains one of the earliest works of literature, the identity of its author is shrouded in mystery. Scholars continue to debate whether there was a single individual who penned the story or if it evolved through various stages over time. The poem itself exists in multiple versions, with the earliest surviving tablets dating to the 18th century BCE during the reign of the Babylonian king Hammurabi.

The version most familiar to modern readers, however, was compiled in the 7th century BCE by the scribe Sin-leqi-unninni, a figure whose identity is mostly unknown but whose work played a significant role in preserving the epic for posterity. Sin-leqi-unninni, however, was not the originator of the story. The tale of Gilgamesh existed long before his time, existing in oral traditions and in fragments on earlier Sumerian tablets that trace Gilgamesh’s exploits as early as the 3rd millennium BCE.

The version most familiar to modern readers, however, was compiled in the 7th century BCE by the scribe Sin-leqi-unninni, a figure whose identity is mostly unknown but whose work played a significant role in preserving the epic for posterity. Sin-leqi-unninni, however, was not the originator of the story. The tale of Gilgamesh existed long before his time, existing in oral traditions and in fragments on earlier Sumerian tablets that trace Gilgamesh’s exploits as early as the 3rd millennium BCE.

It’s also worth noting that the poem itself is not simply the work of one author but rather a compilation of earlier texts, mythological stories, and legendary accounts, refined and expanded upon over centuries. In this sense, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a living, breathing work that evolved with the times—shaped by the hands of many scribes and storytellers who infused their own cultural and philosophical viewpoints into the narrative.

Thus, while we may never know the exact identity of the original creator of Gilgamesh, we can appreciate that this ancient text is the product of a collaborative process. The poem’s survival is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling as a means to explore and preserve human wisdom across generations.

Thus, while we may never know the exact identity of the original creator of Gilgamesh, we can appreciate that this ancient text is the product of a collaborative process. The poem’s survival is a testament to the enduring power of storytelling as a means to explore and preserve human wisdom across generations.

The Epic of Gilgamesh’s impact on later literature cannot be overstated. Its echoes can be found in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, in the Bible’s tales of Noah and Job, and in works as diverse as the Divine Comedy of Dante and Paradise Lost by John Milton. Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality and his final acceptance of death resonate across time, and modern readers often find themselves reflecting on the same existential questions posed millennia ago.

While the Epic of Gilgamesh was first etched into clay tablets, its lessons are eternal. The ancient Mesopotamians may have believed the gods controlled destiny, but the human desire to understand the world, to grapple with suffering and loss, remains as universal as it ever was.

As we continue to face the complexities of modern life—our struggles with mortality, our search for meaning, our bonds with others—the Epic of Gilgamesh endures, not just as an ancient artifact, but as a touchstone for understanding the very essence of what it means to be human.

While the Epic of Gilgamesh was first etched into clay tablets, its lessons are eternal. The ancient Mesopotamians may have believed the gods controlled destiny, but the human desire to understand the world, to grapple with suffering and loss, remains as universal as it ever was.

As we continue to face the complexities of modern life—our struggles with mortality, our search for meaning, our bonds with others—the Epic of Gilgamesh endures, not just as an ancient artifact, but as a touchstone for understanding the very essence of what it means to be human.