The Seventh Seal

Ingmar Bergman’s films resist the category of entertainment. While mid-century cinema often leaned toward spectacle, diversion, or social realism, Bergman approached film as a philosophical instrument. He transformed the screen into a site where theology, psychology, and aesthetics converge—what André Bazin once called the “ontology of the photographic image” becomes, in Bergman’s hands, an ontology of doubt.

Born in 1918 into a Lutheran household in Uppsala, Sweden, Bergman’s childhood was marked by ritual discipline and religious authority. This environment furnished the raw material for a career defined by explorations of guilt, repression, erotic desire, and the possibility—or impossibility—of transcendence. Pauline Kael once described Bergman as a filmmaker who “makes his anxieties our own,” and indeed, from his earliest works of the 1950s through his later meditations, he dramatized inner life with an unflinching intensity.

The scope of his oeuvre is striking. Wild Strawberries (1957) constructs memory as a narrative architecture, its protagonist moving through dream sequences and recollections that collapse time into a fragile present. Persona (1966), perhaps Bergman’s most radical experiment, deconstructs identity itself, anticipating later post-structuralist discussions of subjectivity. As Susan Sontag noted in her essay on the film, Persona is “a work of art that cannot be exhausted” because it stages the very instability of interpretation. Later works such as Cries and Whispers (1972) deploy color and silence with surgical precision, transforming death and grief into aesthetic forms that feel at once intimate and ritualistic.

Bergman’s style—his austere lighting, close-ups that resemble psychological x-rays, and long silences—was not ornamental but essential. It gave visual language to the confrontation between human fragility and metaphysical uncertainty. As film scholar Peter Cowie observed, Bergman’s cinema “speaks with the authority of art that has wrestled with its own necessity.”

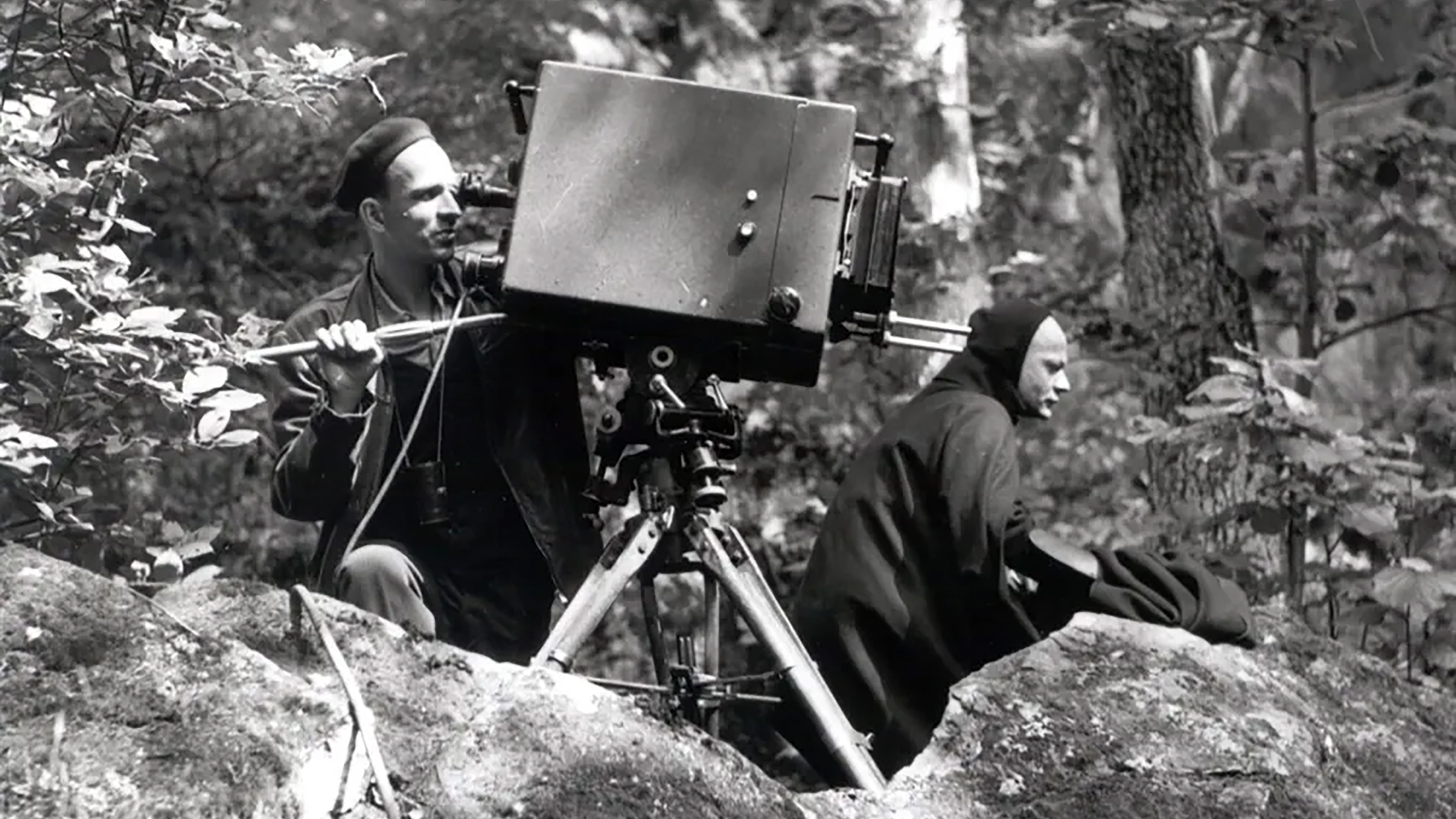

Among his works, The Seventh Seal (1957) remains the most indelible. A knight returning from the Crusades encounters Death on a desolate Scandinavian shore and challenges him to a game of chess. This sequence, spare and iconic, has become one of cinema’s most recognizable images. More than allegory, the film enacts a philosophical inquiry: how does one affirm life when the divine remains silent, and mortality is inescapable?

The significance of The Seventh Seal lies not only in its imagery but in its intellectual ambition. In the shadow of post-war Europe—where faith in progress had been shattered—the film gave visual form to existentialism’s central dilemma. Like Sartre and Camus in literature, Bergman in cinema confronted the absurd directly, insisting on the dignity of the struggle itself. The knight does not defeat Death. He cannot. But in playing, in questioning, in resisting silence with dialogue, he embodies what Bazin once argued cinema uniquely reveals: the persistence of human presence against time’s erasure.

To engage with Bergman, and especially The Seventh Seal, is to encounter cinema as philosophy—an art not of escape, but of reckoning.